Wrenches turning again

A vision for the Camaro’s next iteration has come into clear view, and progress has begun.

More details later – in the meantime, I’m reminded of a passage from Peter Egan I read a long time ago. His context was one of restoration vs. modification, but much of the things are the same. Though today, getting the pieces brought together is a mixture of modern online shopping with phone calls to cottage industries and folks who sometimes, were there for the heyday of the Trans-Am and Can-Am series.

Knowing all this, I paused. Walked around the car many afternoons, gazed at the dirty engine under the hood, tapped fingers on a faded fender, jingled the change in my pocket and tried to assume the bleakest possible expression of realistic hardheaded disinterest.

A car restoration, like marriage, is not to be entered into lightly. It is a fork in the road.

If we look at an old car in need and do nothing, it just sits there. The sun rises and the sun sets. Seasons come and go. The robin builds its nest, morning dew drips from a pitted chrome bumper, children grow up and need bigger shoes, and sediment in the sediment bowl turns to anthracite. A clock ticks on a wall and old men sit on a park bench and watch shadows lengthen in the town square. The car gets older, your checkbook sits on the dresser. Nothing changes.

Not restoring a car is almost the perfect embodiment of stasis. It makes a stagnant pond look like a three-ring circus.

But if you take the other fork in the road, toward restoration, everything changes: your life, your finances and the destinations of a hundred UPS trucks. It is, as Marcus Antoninus said, “like letting slip the dogs of war.”

A set of narrow whitewall tires is shipped across the country; a water pump in Cleveland gets taken off a dusty shelf by a Clevelander and sent to a Wisconsinite; telephone calls in search of superannuated oil seals crackle across a continent; a man in a Texas scrapyard pulls the front bumper off a car rear-ended when Lyndon Johnson was president; old oil comes out the bottom of an engine and new oil from new cans (for today’s higher-revving engines?) goes in the top. A bright orange oil filter spins into place, and a huge breaker bar is unlimbered from the bottom of a toolbox; Liquid Wrench flows like champagne; clean amber brake fluid courses to the car’s four corners, pushing brand-new brake shoes against freshly turned drums.

For sheer unleashed energy, it’s like one of those World War II propaganda newsreels showing American industrial workers giving Hitler a bust in the chops, everything spinning, gushing and throwing off showers of sparks. Tanks and airplanes on parade. Stand back! We are in motion here and we will not stop. We are on a holy mission and our eyes have a zealous glaze; we never sleep.

Car restoration is its own life form; the decision to go ahead and do one is a strange pivotal moment, a headlong act of resolve and suspended logic combined, like lighting the fuse for the first cannon shot at Fort Sumter.

Blow out the match and life remains simple and quiet. Maybe a little too quiet. Light the fuse and there is no peace in the world until the car is restored and rolling. In the meantime, all is glorious havoc.

It’s back!

Got the Camaro out of storage today. The Z is pretty much “done” for now, so they traded places. Mag wheels overdue for a polish, and it hadn’t been run in a long time. Fortunately it started right up and made the drive home just fine.

Not sure what’s next but it’s nice to have it back – distance makes the heart grow fonder and all that. I’d gotten pretty burnt out working on it after 2013 – putting the Z together for STR was a refreshing break.

Lots of potential places to consider as targets for its next iteration. STU, STP (for non-National competition), CAM (also non-National), ESP, SM, CP? Make it even more like a Penske/Donohue close with a cage? Maybe some non-SCCA stuff?

For now, just gonna get those wheels shiny again 🙂

It’s been two years!

Well, it’s officially been two years since I flew up to Sacramento to drive this thing home:

It’s come a long long way since then. I broke the project into five phases:

- Disassembly/teardown

- Fabrication

- Body & paint

- Assembly

- Tuning

Phase 1 finished pretty quickly, I had the car stripped to the shell and off to John Coffey for fabrication, in just over 2 months – November 2010.

Phase 2 took 5 months, to the end of April 2011. A little longer than I originally anticipated, though not really all that long in retrospect. There may be a couple other things I need to have John fab up for me, but the key chassis elements are done.

Phase 3 was the one I feared the most – “paint jail”. We’ve all heard stories of guys with project cars sent off to the body shop, never to return. Pat Smith of Pat’s Custom Cars did a fantastic job in producing a quick turnaround, he had the car a bit over 4 months. Some of the speed might have been due to the solidity of the base car – very little metal repairs were needed, all the original panels were kept intact. Car was hope by September of 2011.

Phase 4 is where it’s been for the past year. Those that have done one of these can appreciate how long this part takes when you’re taking the time to “do it right”. Lots of things don’t fit right without a little tweaking, and it takes a long long time to get all the details done right. When you’re putting this much work into something, any little imperfect shortcut will be staring back at you forever. In addition to the sheer amount of work this step entails for me, life has been busy – the day job/career has been going well but consuming 60-70 hours/week pretty routinely. Earlier this year during my project’s pause, I started a new business and have been working to get it off the ground. Oh, and then there’s this guy:

What was a tiny few cells rapidly dividing when I bought the Camaro, is now almost one and a half years old.

Still chipping away at the to-do list. Even as things get knocked off, it hovers around 50 items long, as I discover new things along the way that need doing. I’ve also been cheating a bit, making some suspension tweaks along the way. Those parts could wait until after the car is on the road as part of the final Phase 5, but many of the tweaks are fun and simple to do, good projects when there’s only 30-40 minutes to work on things.

Usually after 2 years I’m thinking of moving on to something else – in this case, just getting started! The car should provide for a lot of fun for a long long time, in lots of different types of events.

To those that have been following the project this whole time, thanks for your patience!

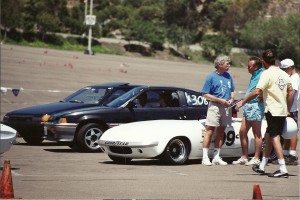

Blast from the past

Got a call the other day from a fellow in Oregon, who was working on a 240sx, and found some paperwork with my phone number on it.

Turns out my car was bought by a family there, and the young man of the family has been campaigning it in their local drift series – winning all the events he’s entered so far-

Car looks pretty good still, much as it did. Wheels and tires are a bit narrower, and it’s got a cage. Still the same funky hood and Tire Rack sticker.

Too bad I never took it to Nationals – a 240sx won the SM Championship this year, I think my car could have won it too. Oh well! Happy to see it’s getting some good use out there, and I asked the fellow to try to get the new owner out to an autocross to learn some real car control! 😉

Why are old Camaros always so slow?

Them be fightin’ words in some circles but since this is my blog, it’s a fair question to ask. The context of the question today, is around why they’re slow in autocross, when seen from the eyes of a typical die-hard SCCA competitor.

One of the more interesting aspects of this project, has been the speculation and conjecture on why the car is going to be slow in STX. As a car builder, one ought to understand their platform, and in leveraging available allowances, do everything possible to minimize the impact of any deficiencies, while accentuating the strengths. We all *know* these Camaros are slow at dodging cones – but what specifically makes them so slow? Some are convinced it’s the axle-tramping rear suspension; others are sure it’s the front suspension, still others think the car won’t really be making good power vs. its competition because of optimistic 60’s SAE Gross vs. today’s Net HP ratings. Or maybe it’s way too big and heavy, maybe the brakes can’t be made to work, maybe the steering is too slow.

Well, I am sure there are many possible reasons, and until I’ve got it running and tuned as well as I think I can, we won’t know which of the above are true. Maybe none of them apply if the car is built right; maybe all of them are true, regardless of all you do (at least within ST rules).

Though I haven’t gotten too far with it yet, there are two Very Big Things I see holding these cars back in the majority of cases, that I’ll address in this post. Hopefully with my advance knowledge of these shortcomings (queue G.I. Joe) and some efforts made in mitigating them, I can overcome. Here they are below, in no particular order-

BIG THING THAT MAKES EVERY AUTOCROSS CAMARO YOU SEE SLOW #1:

The person tuning and driving that Camaro you see, doesn’t know what they’re doing and/or didn’t build their car to “go fast”. Now, I understand that statement comes across as horribly arrogant, but let me explain-

We all (or most guys, at least) tend to think we know what we’re doing the first we get behind the wheel. “Of course I’m an excellent driver”, and we continue to believe it until we see the times of somebody who really is fast.

To use one of my favorite memes in illustration,

| First I was like- |

|

| so I was like, |

|

| but then I was like- |

|

You just don’t tend to see the really fast guys driving old Camaros at SCCA events, and you almost never see the really fast guys at non-SCCA events. They’re often running more modern and closer to stock Miatas or Corvettes, or whatever the hot car is that year. The best drivers tend to flock to the platforms that are believed to be competitive, because they want to win! It’s super rare to see somebody really good (and please, don’t for a second take that to mean I think I am) driving an oddball platform. What this means is the general Good Driver rule still applies to Camaros- a “really good” autocrosser could hop in the driver’s seat of a “beginner/intermediate” Camaro autocrosser, and usually beat them by a few seconds on 50-60 second course. In some ways the non-competitiveness of Camaros, and many other interesting cars, is a self-fulfulling prophecy, as those who own them are likely to get discouraged by their early results and lack of any evidence they’ll ever be competitive, leading them to to not stick with the sport long enough to get any good at it. Who knows, perhaps with some success maybe I can change that – I sure see more Nissan 240sx’s out there today than I saw before 2006.

So there’s the driving element – if the person driving that Camaro wouldn’t be competitive in the Miata or Corvette or whatever, there shouldn’t be any expectation they’ll be fast in the Camaro. Subtract a few seconds for a really great driver, and maybe the car looks a bit less bad?

The other aspect of this relates to tuning and preparing the car to go fast in autocross, and skill in this area almost exactly parallels driving, though most people seem a little more willing to admit their shortcomings in this space.

There is an unbelievable quantity of parts out there for these cars, as they’ve been undergoing speed tweaks for over 44 years now. While as best I can tell the majority of effort into these cars for decades was around drag racing, the idea of making them go fast around corners has become very hot in recent years and the parts variety reflects this. The “handling” renaissance begat a staggering quantity of suspension parts but not a lot of good guidance on what to do with them. Individuality, limitless modification options with no rules boundaries, and differing levels of willingness to sacrifice street manners on the altar of speed, have prevented the crystallization of a “spec” setup for the Camaro. A good example of a spec setup, is that for the super-popular Street-Touring 1989 Civic Si, published by Chris Shenefield about 8 years ago:

http://www.redshiftmotorsports.com/RedShift%20Tech%20Page.htm

With no spec setup to start from and no prior experience assembling a proper-handling autocross car, it’s no mystery so many of these cars end up not working very well, driving aside. The Camaro as a platform is a deep dark hole to climb out of, too difficult to expect anyone to succeed with as their first autocross tuning project. You can put your faith in what your suspension vendors tell you, but their answers are going to be targeted to the middle of their demographic, who may care more (or less) about a comfortable cruising ride, than you do.

There are some people floating around out there in the old-Camaro world who kinda know what they’re doing around the cones, I think, but since there isn’t really any sort of rules in the old-car specific events, it’s impossible to tell who’s doing a lot with a little (bit of modification), or who’s doing less, with a whole lot more. Structure and rules are frowned upon in those circles, which is a shame because it makes results impossible to use in drawing conclusions.

I guess as a message to all my fellow old Camaro owners out there – if you really want to be fast in your Camaro at the autocross (and largely also, the track) – the best thing you could probably do, is park the Camaro for a while. Get a Miata, or an S2000, or a Corvette, and go run a ton of events (SCCA preferably). Figure out who the fast guys are in your region and track your times against theirs. Even better if you get a similar car. By getting a car that’s great out of the box, you can forget about setup and focus on driving. This will teach you the importance of driving, while at the same time familiarizing you with the characteristics of a proper-handling car. When you’re ready, then go back to the Camaro – I suspect the experience gained in a “good” car will better illustrate how far you have to go with your Camaro. It should also help you better understand the importance of different modifications, and get you to spend the next few bucks on tires or shocks, instead of a supercharger.

How am I going to avoid this common problem? By drawing on my experience as a driver and a tuner from many other cars, to dig this thing out of the deep dark hole it starts out in. I don’t have any success stories to look to, but that’s part of the fun/challenge.

BIG THING THAT MAKES EVERY AUTOCROSS CAMARO YOU SEE SLOW #2:

The stock front suspension really is as bad as you’ve heard. There’s a lot of things wrong; below I’ll attempt to explain just one facet of the wrong-ness 🙂

Most of the old Camaros you see at the autocross look awful – they are too soft, and the front suspension looks like it’s doing the opposite of what it should.

Not trying to pick on this car or driver here – this photo pulled from http://www.milesspeed.com/ – a neat site I stumbled across in researching these cars. Car is owned/driven by cool chick Liz Miles, and this was taken very early on in the car’s development. Using it just to illustrate some of what’s wrong with the car’s front end; odds are if you’ve seen an old Camaro on an autocross course, it looked a lot like this.

Here’s another one from a 1967 magazine article on the original Z28:

That thing has no grip on the crap OE tires, but it still manages to showcase how utterly whacked its front suspension is.

Front grip is tremendously important in autocross. At the track if you’ve got way more power than everyone else, you can maybe get away with a pushy (understeering) car, heck, it’s more stable. But not in autocross. You need to generate big yaw/rotation, and you need to be able to change direction quickly. The front tires do all this work and it’s the front suspension’s job to keep the tires as happy as it can.

Pretty much nobody with one of these old cars is giving them enough front tire. I’ve seen cars with $10k+ in aftermarket grafted-on C6 subframes, uber expensive shocks, and mega-$ forged wheels … wrapped in 245 width tires! With 335s out back! That sort of stagger might work on a 911, with over 60% of its weight on the rear axle, but it’s a recipe for terminal understeer (and a frustrating/boring driving experience) in a 55% front-weight Camaro. If you want one of these things to turn, you need to give it all the front wheel/tire you can, and nothing made today with a DOT stamp is “too much”. My Viper had about the same front weight as most of these Camaros, and it had 335s up front! At that size things were just starting to work right. 🙂 Obviously packaging is a problem but with all the effort put into everything else, I don’t see why more of those guys aren’t running at least 285s up front.

So to the subject of analysis here – the motion ratio – and boy is it TERRIBLE! To many that may not mean anything, so let me attempt to explain. Below is a photo of a stock ’67 Camaro lower control arm. At the far left, the rod illustrates the axis upon which the arm pivots. At a bit past 8.5 inches down the tape measure, are the two bolts that hold the shock. When installed, the spring sits concentrically around the shock. At the far end, just under 16 inches, is the lower ball joint’s pivot point. Though you can’t see it here, there’s a hole for the stock swaybar attachment at about 13.5 inches.

So what’s the motion ratio, and why do I care? Well, the motion ratio, is the ratio between how far the wheel moves, compared to how far the shock absorber (or spring) moves. The further out on the arm the spring/shock attach, the higher (and better) the motion ratio. To calculate the motion ratio, you take the distance from the inner pivot to the spring/shock attachment, and divide it by the distance from inner pivot to lower ball joint pivot. If we round the pictured measurements a bit, we get:

Motion Ratio = 9/16 = .5625

This means, for every inch of wheel movement, we only are going to see .5625″ of spring/shock movement. Okay, so why’s that bad?

It’s bad because we depend on our shocks to damp the motion of both our unsprung (wheel/tire, 1/2 our suspension) and sprung (the rest of the car) weight. The better a job the shock can do, the more consistently loaded our tires will be, the more grip we’ll have, the faster the car will go around the corner, the lower our laptimes. This motion ratio is about 30% lower than the motion ratio of a good modern car.

Below is a pic of a Viper’s front corner – look at how the spring and shock attach waaaaay out on the arm, right next to the lower ball joint:

The Viper enjoys a much much better motion ratio than the Camaro.

Shocks depend on velocity to do their job – if they are not moving, they are not displacing fluid, which means they aren’t doing anything. The more shock travel we can get per unit of wheel travel, the better we can control every microscopic bit of that wheel travel. This also allows us to control things with lower shock forces, which makes it easier to find reasonably priced units.

In an autocross car with a good motion ratio, we’re generally looking for what the shock does at about 3 inches/second on a force vs. velocity graph (explained somewhat here: http://farnorthracing.com/autocross_secrets20.html ). Most of the movements the suspension sees on an autocross course are in this speed range, so that’s where we care about what our shocks are doing. Shock velocities above that speed (bumps) are important too but somewhat less so, they’ll be a subject for a later day.

So getting back to the Camaro – with a motion ration of .5625, we’re only getting about 2/3 the shock travel or velocity, of a “good” suspension car. So whereas they get to build their shocks to work at 3 in/sec, ours have to be doing the same quality of control, with 2 in/sec. The problem is, accurate control and large forces at these low shaft speeds, are very hard to come by – any of the common shocks available over-the-counter just aren’t going to get it done, at least not very well. But wait, it gets worse!

Spring rate by itself is a not very good indicator of how stiff a car is – what’s more useful is the “wheel rate”, or maybe the “natural frequency” of a suspension. Here’s an online calculator if you’re interested to find out yours: http://www.racingaspirations.com/?p=292

Those that have ever ridden in an unladen 1-ton pickup truck, and been bounced all around, have experienced a high wheel rate, and a high natural frequency. The high natural frequency is caused by a very high wheel rate, combined with not much weight on the spring (an empty truck bed). If you’ve ever then loaded up that bed with a few thousand pounds and noticed the truck suddenly rode much more comfortably, it’s not because the wheel rate went down (in some leaf systems, it might actually have gone up) – it’s because the natural frequency has gone way way down due to the weight/load in the bed.

We arrive at wheel rate by taking the motion ratio, and multiplying it by itself – “squaring it”, in math terms, then multiplying it by our regular spring rate. In the Camaro’s case, .5625*.5625=.316. That means that for every 1 pound of spring rate, we are going to have .316 pounds of wheel rate.

Wheel rate and natural frequency are concepts you can use to compare the stiffness of any two cars, regardless of suspension type. You’ll often see sliding scales where 1hz is “comfy street car”, 1.5hz, “sporty car”, 2.0hz “race car”, 3.0+hz “race car with aero downforce” – something like that. Those are really just broad generalizations and by no means limits on what you can do with your car.

If you’re setting up a car to handle well, 2.0hz isn’t a terrible place to start. If you’ve driven other prepared-suspension cars that you really liked, that were of a similar layout (RWD, FWD, AWD), it might be worthwhile examining that car’s frequencies and consider it as a baseline. For instance, my 240sx used a 550lb. front spring when it was in STS (street tire) trim. It had a bit over 700lbs. of total weight per front corner, about 55lb. unsprung. It used a strut front suspension which granted a motion ratio of about .96. Its 550lb. spring netted a ~500lb wheel rate, and with the car’s weight, its natural frequency was around 2.7hz. While this was way higher than anybody is likely to recommend for a daily driver, it wasn’t terrible on the street, but more importantly, it wasn’t so stiff that the street tire wasn’t working well. The car worked great!

If you’re setting up a car to handle well, 2.0hz isn’t a terrible place to start. If you’ve driven other prepared-suspension cars that you really liked, that were of a similar layout (RWD, FWD, AWD), it might be worthwhile examining that car’s frequencies and consider it as a baseline. For instance, my 240sx used a 550lb. front spring when it was in STS (street tire) trim. It had a bit over 700lbs. of total weight per front corner, about 55lb. unsprung. It used a strut front suspension which granted a motion ratio of about .96. Its 550lb. spring netted a ~500lb wheel rate, and with the car’s weight, its natural frequency was around 2.7hz. While this was way higher than anybody is likely to recommend for a daily driver, it wasn’t terrible on the street, but more importantly, it wasn’t so stiff that the street tire wasn’t working well. The car worked great!

A similar calc on the rear of an STS Civic I built, puts the frequency around 3.5hz! Some guys I know are running springs up in the 4-5hz range on the rear of those cars.

So getting back to the Camaro, now knowing the 240’s numbers (500lb. wheel rate, 2.7hz) as a ballpark. With our Camaro’s motion ratio, to get a 500lb. wheel rate, we’d need (500/.316)=1582lb. springs! Even at that rate, our frequency is only going to be a bit over 2.5hz, in some ways softer than the 240sx. To get to the same frequency I’d need springs up around 1820lb./in!

Ugg, now we’ve got not much shock velocity to control our wheel motion, and on top of it, we’re going to have to run crazy stiff springs to get this thing to the stiffness level we want.

There are a lot of things “less than ideal” about the Camaro’s front end geometry – bump steer, camber curves, etc., that I can’t really fix in ST, and that you can’t really fix with the stock subframe. In an earlier post I mentioned my plan for dealing with these was to set the static numbers good and “not let it move much”. You can see now why people hadn’t really tried that approach before – they couldn’t! No normal shock you could buy off the shelf would damp a 4-digit spring given an equal motion ratio; things that stiff were just outside the bounds of people’s thinking. About the stiffest I’ve seen anyone run is 800lb. springs, for a 250lb. wheel rate, about half what I’ve depicted above. It’s no wonder people were so concerned with bump steer and camber curves – at that low a wheel rate, the suspension would experience large (double to triple) the quantity of travel as the more stiffly sprung version, so the negative effects of bad bumpsteer/camber curves would also be doubled or tripled. It also means they had to run their cars a lot higher, which is a Big Bummer for them, we’ll explore later.

So to bring this home-

Bad motion ratio gives shocks poor control of sprung/unsprung motions, leading to inconsistent tire loading

Bad motion ratio creates a lot of suspension travel at “normal” spring rates, exacerbating the problems with the stock suspension’s camber and bumpsteer curves and necessitating higher front CG

How am I going to avoid letting this screw me up? Simple answer – great shocks! The 28-series Konis I have, were originally designed a few years back for high-downforce Indy cars, where there are very large forces needed at very small suspension displacements. Even though an autocrossing ’67 Camaro is a long ways from a recent Indy car, the characteristics needed end up being quite similar. There are many other high-end brands (Penske, Ohlins, Moton, AST, JRZ, Sachs, and more) than can get this done too, Koni just happens to be the one I’m most familiar with. With a little bit of revalving, they are going to allow me to run these really high spring rates, while maintaining good wheel control, something a lower-end shock wouldn’t.

Lots more wrong with front suspension, more to come on that later…

Jerry MacNeish

This Jerry guy knows a lot about these cars. He’s been playing with them since before I was born and in doing so has amassed a pretty crazy knowledge base. Jerry is to Camaros as famed autocrosser Andy Hollis is to the Honda Civic/CRX.

A couple things from Jerry showed up today. First was his book,

“THE DEFINITIVE 1967-1968 CAMARO Z/28 FACT BOOK”

Lots of good details, all Z28 specific, will help ensure I get all the little brackets and details correct. Also confirmed (positively, yay!) a lingering gearing availability question I had.

Link to his books – http://www.z28camaro.com/publications.html

While you’re there, check out this car:

http://www.z28camaro.com/unrest68.html

There’s no shortage of myth and legend of what these cars could do from the factory down the quarter mile. Some say they dogged off the line and couldn’t break 15 seconds in the quarter. Others brag of running 10’s with slicks and headers. Any time you hear stories like this, reality probably lies somewhere between. Jerry’s numbers on that page are pretty good on a car with only a couple little ST-ish things done from the factory. This STX car when done should make a little more power and weigh a good 200 pounds less. 🙂

The other thing in the box was an original mint-condition intake manifold for the car. It was supposed to go straight to the engine builder but what the heck, this gives me a chance to photograph it before the motor is all put together.

Can’t wait to be done with all the dirty scummy parts, and start putting together the nice clean new stuff.

Some background on me

Have some time this Saturday night as I’m stuck here doing work-work, will try to use this opportunity to finish up my background story while juggling a few TBs worth of databases-

My family has always been into cars. When my father was a young boy, the family traveled cross country to visit his grandfather on his farm in Pennsylvania. It was a slushy cold February morning, and on the long dirt road to the farm, covered in half-melted snow, they spotted the grandfather, walking to town to shop, in ratty clothes and worn out shoes. They picked him up and took him home, where he showed them around the ratty farmhouse. The tour ended with a trip to the barn, where buried beneath layers of sheets and blankets, was a spotless ’32 Ford. Apparently my great-grandfather would rather risk frostbite and walk to town, than get his car dirty.

My grandfather wasn’t much different. He worked construction and didn’t have a lot of spare money. When my father was going to college at UCR, they built half the garage into a room, with carpeting, drywall, and AC, so he wouldn’t have to share a room with his sisters. The story goes that after graduation, as my father rolled down the driveway to leave for law school, my grandfather had sawed a whole wall off my dad’s “room” and pulled his 260Z in right on the carpet, before my dad was even to the end of the street.

My father was lucky to be born in the early 50’s in Riverside. My grandfather took him to races at the legendary but now-defunct Riverside Raceway. He got to see the golden age of car racing, the Trans-Am and Can-Am series, live. He got to see Jim Hall’s Chaparrals and Mark Donohue’s domination in the Camaro and later in the 917-30. He became a fan of John Morton and the BRE Datsun 510s. His first car was a black 4-door ’68, already in need of rebuilding despite only being a couple years old.

He’d seen an article on Pete Brock’s own yellow 510 street car, and decided to model his first rebuild after it.

So some years go by and I’m born in 1977. They chose the middle name Garrett, because it sounded nice, or after the turbos my father had seen kick butt at Riverside???

Pretty unexceptional childhood. Some BMX and cross-country running. Enjoyed watching Smokey & the Bandit. My mom daily drives the 510 for the next 25 years. My brother and I learn how to slide into the back seat, under the down-bars of the unpadded Autopower roll bar.

Get a job at movie theater and save up to buy first car, a 1985 Honda CRX Si. Turned out to be a pretty decent choice, got kinda lucky. Father insisted I autocross it, so I did, the first weekend after I got it-

Pre-Lasik me at my first autocross, circa 1994, father’s 300zx in background.

Some old-time autocrossers will recognize this Lotus-

At the event was John Hayes, already a CSP National Champion in a similar first-gen CRX. He was very nice and rode along with me, giving pointers. I remember having a nice spin on my third run, despite being a teenager who already knew it all and was an “excellent driver” 🙂

Mark Donohue won the first race he entered, a hillclimb event in his Corvette. Wish I had a similar story but in reality I was probably mid-pack at best in the novice group.

I autocrossed the CRX for a bit locally. Still in school, my extra income went to springs, swaybars, and some fancy Tokico struts. Ironically, I quit autocrossing largely because there wasn’t a place for my car to run competitively, as I didn’t want to buy the special use “race tires” the serious guys were running on. Why would I fork over a couple hundred bucks for wheels and tires I could only use one weekend per month, when that same money would buy a go-fast part I could enjoy all month long? How my perspective has changed since then.

Some years pass. At some point I swap in a twin-cam 16-valve Acura Integra motor into the CRX, after reading about it in Grassroots Motorsports. I have the Integra motor rebuilt all nice with a port& polish, and also swap in its nicer seats and brakes. The car is fun for a few more years but eventually I sell it and buy a Porsche 944.

I only ever autocrossed the 944 once, in early 2000. Wasn’t so interested in racing, but it had been several years, and my friend Devin had just bought an MR2 Spyder he wanted to try out. The 944 feels big and soft and not much fun compared to the CRX. While I’m there I see a couple of the new Honda S2000s, both red. They are FAST! Not long after that on my way home from work, a silver S2000 passes me as I’m getting on the freeway. Hearing that thing go by me at 9000rpm was insane! My jaw dropped, I had to have one.

So the next day I buy an S2000. Not to race, but because my jaw was still gaping from the impression the silver one had left the day before. Not long after, I take it to an autocross, and that’s when the bug really bit me. This car was CRAZY fun to autocross. Super-fast steering, amazing brakes, and a wonderfully crazy motor.

I get to talking with the other guys with their red S2000s, Jason Keeney and Gary Thomason, who won the National Championship in his S2000 the year before. They both have race tires, are way faster than me, and competing in the big “national” events. I decide this is a lot of fun, so I give it a try and prep my S2000 for national competition.

2002 was my first trip to Nationals. I drove out on a set of Kumho Victoracers, finishing DFL at the ProSolo. For the Solo, I co-drove with Joe Goeke, who had bought Thomason’s S2000 which included its unobtanium blade-adjustable front bar and 28-series Koni shocks. I put Koni 28’s on everything now. I think I finished about 42nd in the Solo, way back from Joe who ends up third to previous National Champ Andy McKee and some up-and-coming hotshoe named Jason Saini.

Around this time I attend my first track day with mostly all S2000s, hosted by Speedventures at the Streets of Willow. The track is a bit different than autocross, with its higher speeds and lack of competition. Although I couldn’t afford to risk wadding up my S2000, I end up being one of the quicker guys there. Maybe due to the autocross experience.

Autocross takes a back seat to track days for a while. Pretty soon I get interested in performing some modifications to make the car faster at the track, but would be easily removable to make the car legal again for Stock-class autocross. Having an interest in aerodynamics, I decide to build a flat-plate spoiler for the S2000:

It gets lots of looks and plenty of laughs, but by golly if it wasn’t fast. Along with a front splitter, the car picks up a bunch of grip and stability. A buddy crashes through a fence trying to match my lap time.

With that success behind me, I decide to go one step further and build a real wing. There’s a big track day at Laguna Seca coming up, and I want badly to beat the Laguna lap time of the 6-figure King Motorsports/Mugen S2000 that pesky Jason Saini had beaten us all up with the last trip there. There was also a big multi-day event called the Open Track Challenge coming up, and with no rules, I figured we could use it there.

The wing is designed after the Chaparral 2E. It’s a huge symmetric airfoil with two angles of attack, controlled by the driver. Hall and the gang used a third pedal (they used automatic transmissions) to actuate their wings, I used a switch in the cockpit to send a signal to a monster Duff-Norton electromechanical actuator, to move the wing between zero and 12 degrees attack. At zero degrees the drag contribution from the wing was near zero, as it contributed no lift or downforce; with a flip of the switch it would angle down 12 degrees and provide monster grip under braking and in corners.

With the wing and splitter but otherwise Stock-class car, I get down to a 1:45, within just a few tenths of Saini’s time in the King car, but just can’t catch him. As providence would have it, fellow CA S2000 owner Dave Kennedy, with the fastest S2000 around (gutted interior, Comptech supercharger, and Dunlop slicks) had a mechanical issue that put him out for the day. As the last session rolls around, we talk Dave into letting me borrow his slicks for a session…

The S2000 was absolutely nuts on the Dunlop slicks, I’d never experienced grip like that before. The car was leaning over a lot more and making sounds I’d never heard it make. I was getting fuel starvation with 7/8ths of a tank.

But the laptimes dropped, by a full two seconds to a 1:43, well clear of that midwesterner’s time. 🙂

Later in 2003 we run the Open Track Challenge. I get to drive two different S2000s, Doug Hayashi’s street-tire shod “Touring 3” red car, with a brilliant suspension setup by Erik Messley, and I also get to drive Dave Kennedy’s “Unlimited 2” silver S2000, now even more gutted, with bigger slicks and the supercharger still spinning. We do really well in both cars, winning the Touring 3 class easily, and coming in second in Unlimited 2, beating out the fast Porsche of Wayne Mello and Rick White. With some electrical quick disconnects, we swapped the moving wing between both S2000s.

The highlight of that week for me was running a 1:27 on the big track at Willow Springs in Kennedy’s car.

The track was a lot of fun, but it was expensive, and the competition just wasn’t the same as autocross. Sure, there was road racing, but I was always worried I’d have to bring home my painstakingly prepared car as a wadded up ball of metal, because of something someone else did. Roadracing in someone elses’s car…sure! 🙂

Around this time my friend Ken Motonishi bought a 1989 Honda Civic Si to compete in the sport’s new “STS” class. This class allowed lightweight suspension mods and mandated street tires. He bought the car in May, I threw some parts on it, and in September, Ken won his first National Championship.

I went from being 42nd the year before in the S2000, to 4th in the Civic. I liked this STS class, it allowed all the sorts of mods I had done to my CRX 10 years prior, without mandating race tires or any sorts of really crazy expensive engine mods.

Ken and I ran the Civic again in 2004. I ran in the tougher STX class, so as not to compete against Ken for contingency dollars. We switched from the Falken tire to the Kumho tires, as Ken had worked out a sponsorship arrangement. Unfortunately the tires just weren’t as good. We had improved the car somewhat but still suffered, I ended up 10th and Ken was even further back.

Some people think I might have done better without the wing I built for the Civic, not so much because I thought it’d make it a bunch faster, but more out of protest of how silly I thought STS’s aero allowances were. It’s 7 years later and the rules are still silly, but at least they’re getting better.

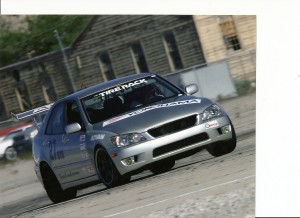

By 2005 I had lost interest in the S2000 despite its continued competitiveness and the Civic was getting a little long in the tooth. Fortunately a couple friends offered co-drives. For the Pro Solo series, Jason Uyeda let me borrow his drift toy, a Lexus IS300. It was legal for the new STU class, and had most of the mods already done. I did some fine tuning of the swaybars, alignment, shocks, and put in a less aggressive limited slip differential. Even with only a couple local events with which to tune it, I won two ProSolo events that year in it.

On the Solo side of things, I landed a crazy co-drive. Gary Thomason had just put a monster motor in what was already a monster ASP C5 Corvette. This is the car that really opened my eyes to what an automobile could do. Everything I’d driven up to that point (and largely, since) paled in comparison to that car. On most couses, you could NEVER use full throttle. The slightest twitch on the throttle would send you spinning off into the weeds. But when you were careful and did everything right, look out! It was just amazing to drive something that immensely capable. I pretty much vowed never to drive anything not RWD ever again.

I never really drove it that well but was getting the hang of it by the second day of Nationals in 2005. I ended up with my best result thus far, 3rd place (albeit a distant third) in SM2, behind that Andy McKee fellow yet again, and the winner Thomason.

At this point I’d been someone’s co-driver every year at Nationals, and figured it was time to take better control of my own destiny. At the time there had been a lot of complaints of how quick the Civics were in STS, and that no other car in the class could catch them. It didn’t help that Ken Motonishi had won again that year.

I had bought the family 510 from my mom around this time. I spent a day in the junkyard pulling parts off a 240z, and bought some things from Ground Control, and did a basic ST prep to it

It was remarkably fast for not having been given much tuning, very close to the Civic’s times. I was convinced in the merits of RWD, but the 510 would have been a dull STS car with no power. I ran a track day with it at Laguna Seca, mostly just to say I did. The alternator wasn’t working and the whole thing was a bit scary, but I still mananged a 1:55.

I decided the 510 wasn’t the way to go, and sold it to my father, who began a multi-year resto-mod project (S15 SR20DET w/6-speed, flared fenders, 13″ brakes, 3-stage Lambo paint, etc., etc. ) that still isn’t done. I’m going to race him to see if I can finish the Camaro before he’s done with the 510.

I’d been brainstorming some potential RWD STS car ideas with friends Uyeda and Thomason. They had both owned 240sx’s, and remembered them fondly. Without putting much thought into what I would do with it when done, I decided to give one a go. I figured the car would be great for the ProSolo series which I enjoy most, as it was RWD and torquey, so it could get off the start line better. I didn’t think the car would be very good in the Solo, as it was at a 650lb. weight disadvantage to the Civics.

To give it the best chance possible, the 240 got some really nice parts, like 28-series Konis from ProPartsUSA, a freshly rebuilt motor, and super light Volks wheels. It was the first car I’d ever really built for myself and I wanted to do it right, and not give myself any excuses if it didn’t work out. I built it up for STS over the winter of 2005 and into spring 2006. It won in its first ProSolo at Fontana

And again the next month at the Atwater Pro. The car had a couple “unfair advantages”, if you could call them that. First, it was rear wheel drive and had a limited slip differential, and was basically the only car in existence that had that combination and was still legal for STS. The other advantage was the 240 could leverage the newer and better tires. I’d had a taste of the new Yokohama Advan Neovas tires the year before on the Lexus, and knew they were a cut above the Falkens and Kumhos the Civics were still forced to use. Fortunately for me, the new tires weren’t offered in the smaller sizes until after 2006.

The car was really dialed in by the National Championships, and I won the ProSolo Finale with a big margin, over 1.2 seconds. That was my first National Championship of any sort and really felt great – the vision of the 240 as a ProSolo winning car had been realized. Next came the Solo Champsionships, which is generally more talked about and more esteemed than the ProSolo champsionship. After the first day I was a ways back in second place to Jason Frank in his Civic. Jason drove really great on day one, but unfortunately it was found that his car was missing a bunch of sound deadening stuff for which there was no allowance to remove. The protest committee decided to disqualify Jason and his codriver Craig, which was really harsh. It was unfortunate too for STS as a class, as the year before, the quickest Civic had been DQ’d for having its catalytic converter in the wrong place by just a few inches. The penalty for violating rules in autocross can be rough!

On the second day I managed to keep what was now a lead, and posted the quickest time in the class. It was really a bummer situation for everyone, Jason and Craig I thought were great sports about it. While I hadn’t “won” the National Championship in the way anyone ever hopes to win, I did at least show the 240, and perhaps other oddball cars, could be competitive.

At this point I realized I had made the mistake of dumping a bunch of money into a car that nobody with a bunch of money would ever really want to own. It was fun, modestly fast, and reliable, but now what? The 240sx community was very into turbocharging their cars, as it came with a turbo from the factory, if you were in Japan. I decided to “throw good money after bad” as they say, and go to Street Modified.

The Street Mod buildup of the 240 was a ton of fun. The car became like a laboratory kit, where I got to learn about turbocharging, engine management, and cutting fenders. I designed the turbo system, built all the charge pipes, and did the base tune on the AEM engine management system. I cut the fenders and fit huge race tires, added a better limited slip, and did a bunch of things to get weight out of the car. The end result was pretty nuts-

I’d also had an aero engineer in the UK design a 2-element wing specifically for my application and got to learn a bit about modern composites when building his design out of carbon fiber

But the car overall was very high maintenance. In an extreme effort to minimize lag, I had utilized a low-volume ice-water/air intercooler, with an enclosed fish cooler in the back seat. This kept the volume of charge pipes very low and intake air temps super low, but was a huge PITA. It would melt 10lbs. of ice in one run, and the water would be warm after two. This required lugging around huge amounts of ice, dumping all the warm water somewhere, etc.

The car needed race gas, to be trailered everywhere, and just a lot of attention in general. It was a blast to build but awful to live with, even if it was putting down scratch times towards the top of the class in its first outing. Around this time I started thinking I needed to buy a new house, which is no small order in San Diego. So instead of continuing on with the 240, I put it up for sale. It ended up selling for not much money. It was the first car I’d really built up myself, and I really learned the hard way what happens when you dump a bunch of money into a low-$ platform. Oh well, I only lost about the equivalent of a years’ worth of college tuition, and I think what I learned from the 240 was more valuable than a year at college… 🙂

Knowing I would be busy for a year or two with a new house and landscaping and all that comes with it, I knew I’d need a car that wouldn’t need a lot of attention. It had to be something I could get in, drive, put away, and not look at it again until the next race. I’d also been eye-ing the Super Stock class for the past couple years, ever since Matthew Braun won it in 2006. There was a super fast class with a ton of highly skilled drivers. In keeping with my approach of using different cars, I decided a Viper would be the way I’d go. I did some thrust and tire loading calculations, and figured the car could get in the ballpark with the C5 Z06, which was still an SS top dog.

Originally I’d wanted to get a Gen2 (’96-’02) Viper GTS, as it came with a proper clutch-type limited slip, and was a cooler looking car than the Gen3 (’03-’06) Viper. However, fellow autocrosser Scotty White had his 2004 Viper for sale for a good price, so I drove up to Washington and got it out of his truck yard.

I didn’t have much time to race in 2008 and only did a few events. The car showed some competitiveness, even though all I had time to do was build it a custom front sway bar and throw on some Hoosiers. Gary Thomason ended up winning the class that year in his GT3 after yet another epic SS battle.

2009 rolled around and the landscaping was just about done, so I turned to giving the Viper some attention. I again worked with ProPartsUSA to put together some 28-series Konis. I got last year’s and many-multi-time champ Thomason to co-drive with me. We didn’t do so well at El Toro, due to adjusting to the Kumho tires Gary was able to provide. The shocks went on the car after at El Toro, and it was transformed for Wendover. The car became a slaloming machine, able to dance through the transitions, of which there were many. Gary showed his prowess and won in Wendover by a big margin.

For 2009’s Nats I had another trick in mind, to switch from Kumhos to an even bigger Hoosier than I’d tried before, a monster 335/30-18 front. The car was just amazing with that tire setup, and after the first day, Gary was in a close second place, I was not too far back in fifth. We’d been scrambling to make some adjustments for the new tires, and were all set to rock on day 2, when it rained. The first few drivers got dry-ish runs, and Gary, driving first, managed to hold on to second place, but the course was soaked by the time I ran. What bad luck! I think I took it okay, as I had been the recipient of some unusually good luck in 2006, and that sort of luck seems to have a way of balancing out in the end.

2010 started off well with a strong showing at the SD National Tour, where I would have won the class if I’d run in it, but had to run elsewhere due to scheduling conflicts. Was a close third at the El Toro Pro, couple small mistakes kept me from winning. I was starting to learn that SS wasn’t a class where you could have mistakes and expect to do great. Wendover was even worse, as the tires were a bit past their prime.

I had some more good luck of sorts in August, I was contacted by Mark Jorgensen of Woodhouse Viper in Nebraska, letting me know that Dodge had decided to hear my plea, and grant supercedence on the diff for my car. I’d been lobbying with Dodge and SRT pretty much since I got the Viper, to issue a part supercedence, allowing the Gen3 Vipers to replace their limited slip diffs with the much-improved Gen4 part. We don’t have any sort of update/backdate allowance in Stock, but are allowed to go to revised parts when the manufacturer issues a supercedence. I had the part in the car within two weeks of the issuance, and could tell it was much improved.

Day one of Nationals 2010, I ended up making one single, but big mistake, that would end up costing me the championship. I had to stand on a run that was about 7 tenths slower than my time should have been. I was still in the hunt, but day 2’s course was much more narrow and transitional, and I knew I wouldn’t be taking home the jacket without going into day 2 with a lead.

At least day 2 went well.

My first run that day was the best I’d ever driven the Viper, and maybe the best I’d ever driven anything. It still wasn’t as fast as Matthew in the Elise, but moved me up to second place, a ways ahead of third. For the first time ever I felt like I was in the “fast guys club”. While not a perfect ending to the Viper chapter, it wasn’t a terrible way to end things either. The Viper sold quickly for its full asking price and went straight from Nationals to its new owner in Texas.

I’ve got some time again to work on cars, and am looking forward to building the Camaro. I enjoy the ST level of preparation, and the STX class offers a great mix of cars with some really fast drivers. This is a much longer longshot than any of the oddball cars I’ve done before, but the tinkering aspect is really my favorite part of the sport and at the very least, this thing should keep me engaged for quite some time.

The Rules

On 10/13 I removed this long boring post, and made it into a page you can access at the top or the side of the blog.

http://www.rhoadescamaro.com/build/?page_id=260

Been receiving a few rules-related questions, hopefully this makes it easier for those folks to find and read through the rules, maybe get their questions answered in advance.

Some groundwork on cars and rules, philosophy of boundaries and identity and purpose

The purpose of this project is to construct a ’67 Camaro that can win the SCCA STX Solo National Championship. To do that I’ll have to beat some very fast drivers in much more modern cars – the Mazda RX-8, BMW 328, Subaru WRX, and 1989 Honda Civic Si (those not familiar with autocross will wonder about that last one, it’s a long story…)

In doing so I have to adhere to the rules of the STX class. Along the way I am going to have lots of problems making the car work as well as I need it to within those allowances. Here are a couple links too, the rules may change a little over time, depending on how long this thing takes to get put together…

Those not accustomed to this sort of competition are likely to think to themselves along this road “why don’t you just cheat and do X”…”nobody will be able to tell if you do Y”..”just do Z, they’re probably doing it too”. None of those thoughts are going to fly here. SCCA Solo is a much different sort of motorsport – there is no “tech inspector” to try and fool with illegal modifications – it is a competitor policed sport, and all your competitors, who are also your friends, are relied upon to make sure your car is legal. I think this is part of why there really isn’t that much cheating in Solo – if you did, you’re really cheating on your friends. In roadracing, where all the best cheating stories come from, there’s much more of an “us vs. them” mentality, and people probably take getting away with having “outsmarted” the inspectors, with pride.

Others may wonder why I’m choosing to limit myself to what is a fairly low level of modification for a platform that you often find extensively modified. Part of the reason is I’ve built two winning cars to this level of preparation before, and enjoy what it allows me to do, while not making me do anything I don’t want to do…like cut up the car to fit huge tires. In the case of the Camaro, there are actually a surprising number of similarities between the ST Solo category, and what Donohue and the Trans-Am racers were allowed to do back in their day. I am a huge Mark Donohue fan, and part of the wacky appeal of this car to me, is that when I’m done, the car should extremely similar performance to what he experienced back in the late 60’s. If I do it right, maybe even slightly better performance… 🙂

(this is a totally irrelevant picture of the crummy motor that came in the Camaro, in the middle of a compression check. Had to break up all this ugly text with a pic! Motor going on craigslist soon)

Of course, there are more things one can do to make a car faster than what I’ll end up with. I think at some point though, the more a car is modified, it begins to lose its identity. Everyone has a different line where they feel a car loses its identity, and for me, it’s not far beyond where I’ll be going with this car. Sure, it could handle better if I replaced the frame with C6 stuff, and it would make more power with a new LS9, and there could be huge improvements moving the firewall, back-halving and mini-tubbing the car, rack-and-pinion steering, etc. But would it still be a Camaro? Is a new C6 with a first-gen Camaro body on it a Camaro or Corvette, does it even matter? I guess my point here is, the STX rules are a place I feel allows me to make the car all it can be, and a ton more fun to drive, without sacrificing its identity. When you’re operating in a world without rules or boundaries, if you want the fastest drag Camaro, you take your Camaro’s firewall identification plate and slap it on a top-fuel dragster; if you want the fastest autocross Camaro, you slap it on an A-Mod car, or for the fastest track Camaro, find a spot for it in an F1 car. Obviously those are extremes, but if you don’t have boundaries, you’re depending on everyone to have their line where the car loses its identity, at the same place.

It also helps the budget, that STX rules are somewhat limited.

The long strange trip

Up at 5am today, hit the airport for 6:40 Southwest 119 to Sacramento with perfect timing. Caused a stir at the bank by trying to withdraw my own money (?), paid the fellow and left in this-

Yes, that is a red/orange overspray on the left front tire. Fellow was doing a quick fix-up and sell, and got a little rambunctious with the paint gun – the windows, engine compartment, license plates, door handles, radiator, etc., all got paint on them. No big deal as most of those things will be replaced or repainted anyway.

So with no speedo and no gas gauge I set off from Sacramento towards San Diego around 9:30am. Car has a V8 out of an ’84 Camaro with an Edelbrock carb. Transmission is a 4-speed, Muncie we think. It’s not too whiny and first seems a little tall and close to second, so I’m hoping it’s an M21. Rear end is a 10-bolt but very steep, thinking probably a 4.10.

With this setup I’m expecting 13-14mpg, even at the guesstimated 55mph I’m traveling. Car had about 30 miles since last fill-up, so I stop about 40 miles in to gauge consumption. Never filled up one of these wacky rear-fill things before, the lack of evaporative emissions gear readily apparent. At about 3.2 gallons, fuel starts spilling out all over the back bumper. That’s odd. The fellow mentioned it leaks a little bit and to hold it tight, so I do, but after about 3.5 gallons, everything I dispense splashes on the ground. Hmmm…

Make it another 110 miles, and I can only fit in 5.2. It is a new tank and the owner said something about the level and rake in the car, so I turn it around on a slight slope, and still can’t fit any more in the tank…

(Can you see where this is going yet?)

The darn thing got 20-24mpg for every leg of the trip. I still stopped every 110-130 miles to be safe, but I never fit in much over 5 gallons. Since I was going to be taking the car apart at home and didn’t want too much gas in it, for the last leg went from the south side of the grapevine, all the way home, about 150 miles.

Definitely plan to get a functional gas gauge going!

So…how was the car on its first drive?

It has manual everything – steering, brakes, etc. The steering ratio feels like it’s 99:1 in parking lots – takes 2 turns to do anything and it’s still heavy. There’s about 1/8th turn of dead spot in the middle, monkeying around with 1/8th turn in the Viper would get you spinning.

The brakes are phenomenally…atrocious. Manual drums at all four corners. The worst brakes of any car I have ever driven. There was a little pull to the left but I have to imagine they probably aren’t much worse than when the car was new. Scary stuff!

Speaking of scary, there were no seatbelts in the car. It had seats from the ’84 Camaro, must have lost the belts in the translation. I’m a big believer in seat belts and always wear mine – their absence is part of why I’m going right to work on this thing instead of tooling around with it for a bit.

Side window vents rock! They did a great job of making window-down a comfortable and quiet thing.

The engine was pretty weak and sounded like it was full of exhaust leaks. The gas pedal required huge force to press, that got really annoying. Not going to miss this motor.

Used the transmission/engine to help deceleration on offramps. It would pop out of third gear under decel. Looks like the trans will for sure need a rebuild if kept.

Got home around 8:15pm, tired, but excited to actually check out the car. Had been in “get it and get it home” mode all day.

Couple scary things – one missing and one half-off lugnut on right front. Other corners have all five. Camaro Berlinetta 14″ wheels have too much offset for this suspension, the lower steering ball joint was rubbing the tires the whole way home.

The wiring is a complete disaster, stuff going everywhere, lying on hot parts, tangled in steering, you name it. Will have to be completely redone.

The thing is SOLID! No signs of rust anywhere with some extensive magnet testing. Looked underneath, the original factory bump stops are there, all the suspension appears unmodified. It even has the original sound deadening under the carpet. This is a great place to start for an STX car, as so much of the original stuff is still there, and I won’t be stuck with the car in “paint/body jail” for 6 months. At least, I hope not.